This post is part of ChicagoNow’s monthly “Blogapalooza” feature where bloggers are provided a prompt and required to write and publish a post within an hour. Tonight’s prompt was this: “Pick a song that has special meaning to you and explain why.”

My Dad’s been on my mind a lot today. Probably because the first thing I saw this morning when I flipped on the old Facebook was THIS – a collection of photos and memories chronicling my Dad’s last months before he died. It was a horrible, horrible time for my family. Something I feel I am still reeling and recovering from in many ways.

Then tonight, dishes done, kids in bed, getting ready to settle in for some serious binge watching of something, anything, our landline rang. Yes, I still have a landline, it’s true.

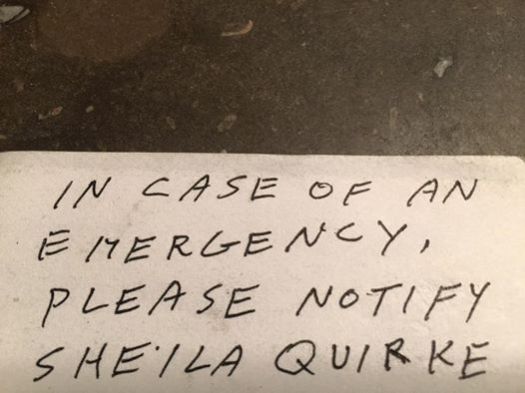

It was a volunteer for the local Democrats looking for my Dad. Inexplicably, I heard myself saying, “John Quirke is dead. May I take a message?” What the what? Not exactly certain how I might deliver that message, but the offer was out there.

The volunteer politely declined, offered his condolences, and clearly wanted to get off the line. Yeah, but no, I was still talking, grateful for the connection to my dead Dad, someone looking for him, calling for him, reminding me that in odd little ways, he was still a part of the world. I started chatting about him, reassuring the man that had my Dad still have been alive, he would have been a lock for Hillary. And I just kept talking, providing more reassurance that my Dad’s four kiddos were also good for Hillary votes. There was an awkward, “That’s great!” from the other end of the phone, then the call was over.

I smiled, thinking that while my Dad wasn’t successful in passing along his deeply entrenched Catholic faith to any of his four children, he did manage to solidly pass along his Democratic faith to those same four kiddos. I wondered, as I never asked, which of those might have been more meaningful or important to my Dad. I honestly don’t know.

I own that while I don’t practice the Catholic faith, I am marked by the cultural significance of growing up Catholic — something that is simply part of my fiber. Familiar traditions, spoken prayers, comforting memories of childhood. As the siblings of my parents die, I will lose my last tangible connection to the Catholic church. My Dad’s funeral may very well be the last time I would step foot in the church and parochial school that was my home from kindergarten through eighth grade. So many happy memories there, so many challenging ones, too.

When my Mom died, my sister and I both delivered eulogies. It was never in question and simply worked into the funeral mass. That same sister and I both expected to eulogize my Dad, ten years later, when we were surprised to learn that families were no longer allowed to eulogize a loved one or provide any kind of personal remembrances at the funeral mass. Catholic practice now demanded that funerals be focused on God and faith, and not so much on the deceased.

Hearing that was crushing, I’ve got to say. I’ve delivered four eulogies in my life and each of them has been my love letter to someone I miss dearly. My personal goodbye, a way to put into words a sliver of what loving them had gifted me in life. I did this for my Mom, then my daughter, my aunt (a nun herself), and had mentally crafted the words to my Dad’s eulogy for the past twenty years, since my Dad suffered his first heart attack at age 60.

My sister and I bickered about it at the funeral home. I was stunned and bereft, full of words that needed to be spoken about my Dad, for my Dad, the last time I would ever stand next to his body before it was committed to the earth. And I was being told no. It was unacceptable.

I arranged for the funeral director to call the priest directly, the same priest from my childhood, a man my father had had a very complicated relationship with after the good father simply forgot to show up to the mass where my parents were to renew their marriage vows in honor of their 25th anniversary. There was a church full of friends and family who had flown in to help celebrate a silver anniversary but no priest, so no vows. Worse was his refusal to apologize to my parents. It put both my very Catholic parents off going to mass for a few years.

Anyway. Fast forward to me literally begging this father, the holy one, not the biological one, to be able to eulogize my Dad. I pleaded and appealed, hoping to find his humanity. “Three minutes,” he said, “I’ll give you three minutes, but then I’m cutting off your mic.” I expressed tremendous gratitude, but all I could think to myself was, “Yeah, peace be with you, too, buddy.”

I laughed after hanging up the phone, remembering, from the fantasy funerals for my Dad that had played out in my head for the past twenty years, that there was no chance in hell I would be able to get to hear the song I had always imagined would play as his recessional — the song that is played as the casket is carried out of the church after the funeral mass. That song being Jim Croce’s “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown.”

Bad, bad Leroy Brown from the southside of Chicago, baddest man in the whole damn town, meaner than a junkyard dog.

That song transports me to my years of childhood, watching my parents dance to it at all of my cousin’s weddings, and I had a lot of older cousins. I loved to watch my parents dance. They had a complicated relationship, my folks, but they always made sense on the dance floor. They met at a dance hall in 1957, the Holiday Ballroom.

So, yes, I didn’t push the idea of Bad, Bad Leroy Brown as my Dad rolled out of church for the last time. I was happy with my three minutes. But tonight, this one is for Da. Take it, Jim Croce, and for those of you at home, this works best with the volume up, way up.