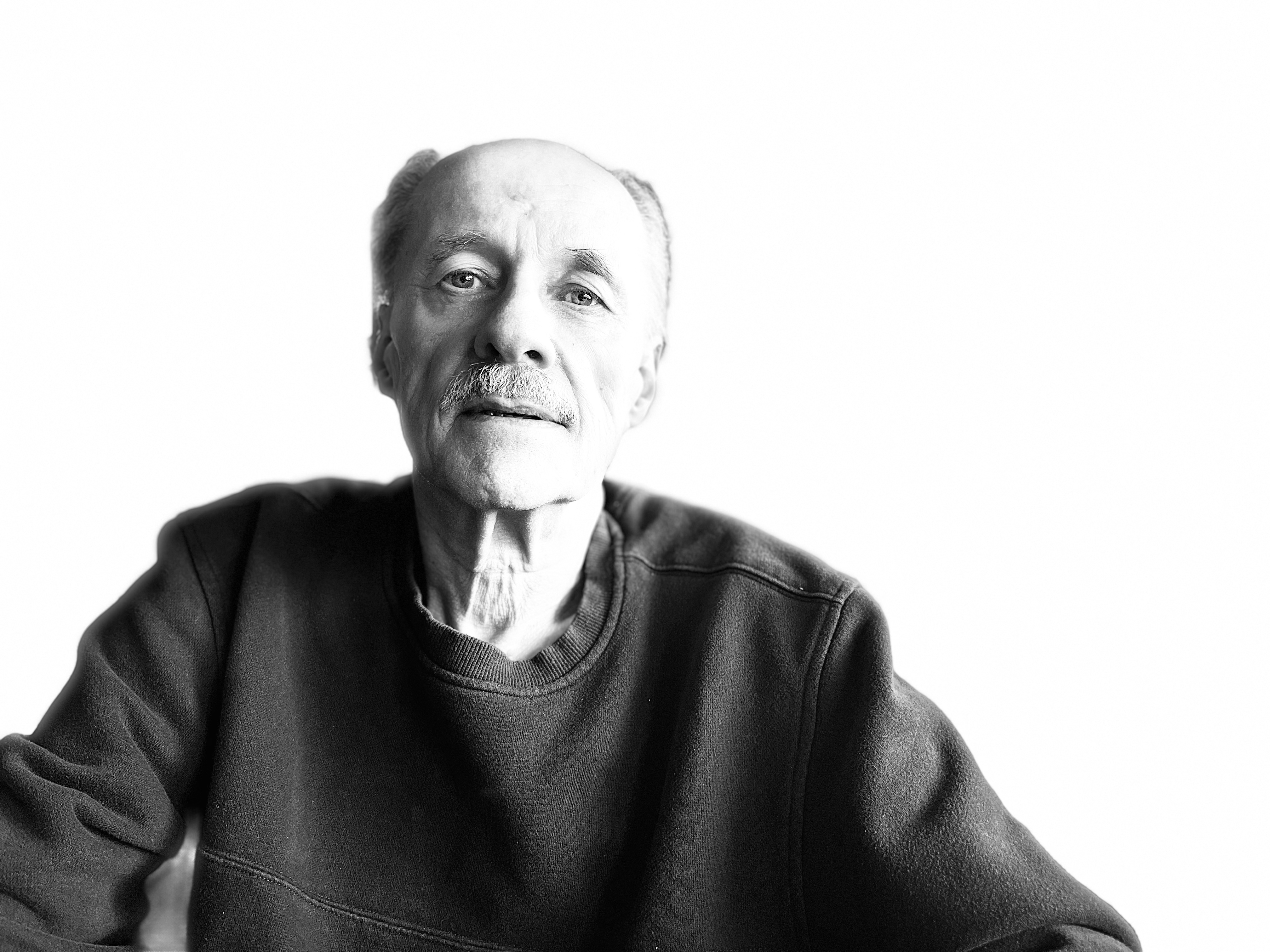

Memories From a 5th Grader

“I did it,” whispered the boy sitting behind Ricky, as he poked him in the shoulder, “I did it.” Ricky did not dare turn around, as he knew it would result in certain punishment from the nun at the front of the classroom and he did not want to suffer the consequences of taking the bait from a kid who had a history of getting himself and others in trouble. Ricky ignored the whispers and pokes from the boy everyone called a “fire bug” as best he could.

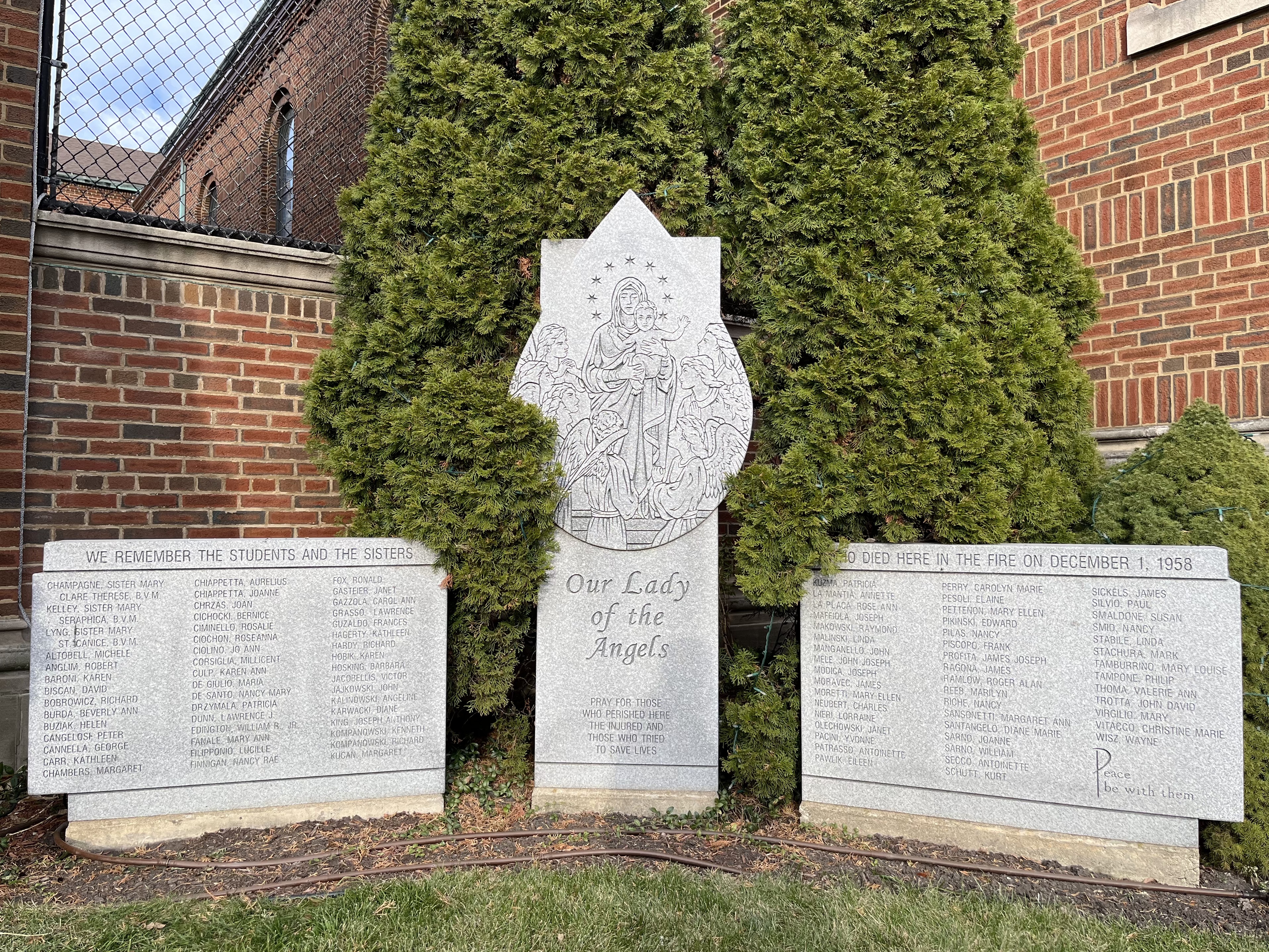

Ricky is now Rick, a 75-year-old man who has lived in suburban Villa Park for almost five decades, but in 1958, he was a fifth-grader at Our Lady of the Angels Catholic School in Chicago’s Humbolt Park neighborhood. The “it” that his classmate was referring to was the December 1 school fire that occurred on that frigid day in 1958 resulting in the deaths of 92 children and three nuns, all teachers.

It remains one of the worst school fires in history.

Officially, a cause of the fire was never determined, but that 10-year-old classmate who whispered into Rick’s ear would later confess to starting the fire during questioning from a polygraph expert and in front of several witnesses. Ultimately, the boy recanted his confession, and a judge threw out the case.

Today marks the 65th anniversary of that terrible fire, that terrible day. For Rick, it still feels like it happened yesterday. He wells up as he talks about it, memories pouring out, clear and detailed.

Like any other day, Rick woke up and got ready for school on December 1, 1958. He had a slight limp from a recent football game and a large bruise on his leg. His mother decided he should stay home. Rick was mad – he had perfect attendance and if he missed a day, he would lose out on the attendance prize, but his mother insisted, “You can help me clean the house for Christmas,” she told Rick.

Rick remembers wiping the blinds in their apartment on North Trumbull when he first heard the sirens in the afternoon. They were deafening. His mother wondered aloud, “What the hell happened? Did the school burn down?!” Rick cheered at the idea, “YEA! Two weeks off of school!,” just as you would imagine a fifth-grade boy might.

Moments later the phone rang. It was his mother’s friend telling her that, yes, in fact, the school was burning down. “My mom went white and dropped to her knees,” remembers Rick, “She begged for forgiveness.” She ran out to the school, telling Rick to stay home, “Your father will be calling and I want him to know you are safe.”

Rick’s father did call. He heard about the fire while riding the bus home after work. A friend gave him a dime so he could call from a pay phone. Just as his mother wanted, Rick stayed to answer that call, reassuring his father that he was safe, though he wished he could have gone with his mother. It was his school that was burning and he was worried about his crush — was she okay? How bad was it? How were his friends?

It was bad. Very, very bad.

Later, Rick’s mother would tell him she saw Fr. Joe (Rev. Joseph Ognibene) “punching out windows,” working to free children from the smoke and flames. She saw many other children jump from the high second story windows, trying to escape.

A history of the fire was documented in the 1996 book, To Sleep with the Angels, by David Cowan and John Kuenster. Rick bought two copies of the book the day it was released, one for himself and one for his mother. He has never read it, but it sits on a bookshelf, an important document of one of his most formative experiences, “Maybe one day I’ll be able to take it down and do more than look at the pictures.”

Because he was not in school the day of the fire, Rick has mixed feelings about it, guilt being primary. His teacher, Miss Pearl Tristano, was the one who pulled the fire alarm, alerting those within the school to the danger. All of her 60+ students would evacuate the school safely. Other students in other rooms would not be so lucky.

“The school was immaculate,” recalls Rick, “There must have been an inch of wax on the linoleum.” It was things like the wax and linoleum that contributed to the conditions that made the fire so deadly. In one of the classrooms that had over two dozen deaths (there were three that logged numbers that high), those who died succumbed to smoke inhalation, not flames.

In the days that followed, Rick’s family, just like the rest of the Humboldt Park neighborhood, the larger city, and the whole country, grieved. “We were sad,” remembers Rick, “Mother and Grandmother were crying. Mom took me to four funeral homes to pay our respects, but after the fourth one I heard her say, ‘What are we doing? This is no good for Ricky.’” They stopped going to funeral homes.

Within a couple of weeks, the 1500+ surviving school children of Our Lady of the Angels (OLA) were back learning, tucked away in a patchwork of schools across the near Northwest side. “School and Church didn’t mess around,” says Rick, “We got back to class very soon after the fire.”

Chicago Public Schools and the Archdiocese partnered in opening classrooms to absorb the kids of OLA. Rick was reassigned to Our Lady Help of Christians on Iowa Street. His teacher, Miss Tristano, was gone and did not return. A nun he does not really remember replaced her.

“Everybody was sad,” recalls Rick of those days, “The whole neighborhood was down. Everybody knew somebody who was hurt or who died.” The mood, he says, was somber.

Rick also remembers that no one really talked about the fire or the deaths. He recalls hearing about one nun who “completely flipped out” and was quietly removed from her teaching duties. Rick describes one night he himself broke down, “I started bawling, crying like a baby on our living room floor, sitting in PJs, cross legged doing homework.”

Now, sixty-five years later, Rick believes he still has PTSD. “There was no discussion of the fire ever. ‘Offer it up to God,’ is what we were told. It kind of bugged me,” says Rick. “For my own sake, I would like to get over it.” To this day, Rick never uses candles and is extremely careful in locating fire exits when he is in public spaces.

“I’ll never forget it, ever,” says Rick, “I think about all the people. They were just too young. That fire was the turning point, for people and for the whole neighborhood. It was never the same again. The togetherness was gone. It’s still an open wound, but December 1 is like a holiday for me, a day to just remember.”

_______________________________________________________________

Author’s Note: I extend my grateful thanks to Rick. I grew up hearing stories about the fire at Our Lady of the Angels School, so it was always on my Chicago Catholic upbringing radar. I interviewed Rick on a completely unrelated matter and, as we are both prone to do, we got to talking. Before I knew it, Rick was recounting his memories of that fateful day. For me, he was like a history book come to life. I am honored to have been his audience in recounting his memories and humbled he agreed to let me capture them.