September is Childhood Cancer Awareness Month. Each day I will feature a different guest blogger who will generously share their personal experience with childhood cancer. Stories are always more potent than statistics. The hope is that by learning about children with cancer, readers will be more invested in turning their awareness into action. Read more about this series and childhood cancer HERE.

By Annie Bares Thomas

We wintered at the children’s hospital that year. It was a colder winter than most, filled with stinging rain and painful memories. I recall bringing Isabelle back to the hospital one night, after she spiked a fever and required urgent medical care due to neutropenia. The sky seemed blacker than usual. The air crisp and biting.

As much as I dreaded arriving at the parking garage, it was also my favorite place in the hospital. It was our limbo. If I was holding Isabelle in my arms in the garage it meant one of two things; either we were at the threshold of the cage-like constraints of being inpatient, about to fly free, or we were heading back in, still with the taste of freedom and home in our very recent memories. I would never mind having to circle the many levels of the garage to find a spot, for it meant we were free for a few more precious moments. My husband Alexis offered to drop us off at the front door. Unless Isabelle was very sick, I always declined. This was such valuable time for me. I savored the last breaths of fresh air, in spite of the added smell of car fumes. Every time I pulled Isabelle out of our rusty, early model Volvo, car seat and all, I’d silently remind myself, “You can do this.”

My usual brisk pace slowed as we neared the east wing. The mechanical swoosh of the automatic doors foreshadowed the flooded heat of the hospital, immediately bombarding us with artificial warmth. The smell of the air on the main floor was deceiving. Fresh brewed coffee from the Java Hut intertwined with chicken from the cafeteria and perfume samples sprayed in the gift shop. Here in the lobby we would see excited people rushing with balloons and flowers to meet a brand new family member, or swollen-eyed groups, leaving the hospital with weeks worth of belongings and one less in their clan. As I held my neutropenic baby, I made sure to push the elevator button with my elbow and not my clean fingers.

We called it wintering because we were in a new and exotic place. Isabelle had never been in a hospital before her cancer diagnosis, for she was born in an old Victorian house under the gentle care of midwives. I too had escaped hospital life until now, as the only time I spent inpatient was as a healthy newborn, back in the 60s, when all babies were kept for a week.

We were treading on new territory.

I grew up in a large middle class family in a west Chicago suburb. No one I knew ever “wintered” anywhere but home. The first reference I heard to wintering was while watching a M.A.S.H. rerun on the black and white TV my sister Maria and I bought with collective babysitting money. During one episode, Winchester met his match with another snooty officer who was visiting the M.A.S.H. unit. As it turned out, the visiting officer was the son of a servant, so his experiences of “wintering” were those of the hired hand. Yet, since he had been to all the right places, he was able to fool Winchester into thinking that he was more refined. Kind of like us. Wintering at the hospital, yes, but so very sure we were not like these other people. We would spend some time here, okay, but we would not stay. Isabelle would move on. She would live and survive. That was the thought that kept our blood flowing and our hearts beating.

***

I remember the day my sister Maria and I planned to purchase that television so well. I was babysitting Leah Simonek. The money I would make from that visit would bring our savings to what we needed to buy our own television set… a true luxury of the time. My dad was to pick me up, with Maria in tow, and we would head off to the Service Merchandise to complete our first major purchase. We had picked out the TV weeks before. It had a goldenrod frame with two big black dials on the front right hand side, one on top of the other. The antenna was long, so we were excited about the possibility of being able to harness nine stations. We longed to have our own television, as it meant we could fall asleep to reruns of M.A.S.H. and the Honeymooners, our two favorite shows at the time.

When my dad came to retrieve me, my sister Maria was nowhere to be seen.

When I hopped into my dad’s car he said nothing at first, other than, “We need to go home.” I was angry and pouting as I knew we weren’t going to the Service Merchandise as planned, but I didn’t say anything aloud, as my dad was strict and not always approachable. Mrs. Simonek, the woman I had been babysitting for, came running out to the car.

“Roger!” she yelled to my dad. “Roger, I had a dream about Liz last night.” My dad stopped her before she could say anything else.

He simply said, “Lizzie passed away today.” Mrs. Simonek burst into tears, gurgled something to my father, and then ran for the safety of her home.

Passed away? What did that mean? I had only known of old people “passing away.” Young girls, like my sister Liz, didn’t “pass away.” As he pulled out of the long drive, my dad turned to me and said, “Lizzie died today.”

I was angry and confused. I knew my sister had bone cancer, but no one ever told me she could die from it. I went to the hospital with my mom the night before, at my pleading, and saw Liz. She was alive and happy. I remember my mom scolding me for eating food off the hospital dinner tray that my sister wouldn’t touch. Liz laughed at me for getting in trouble, as she so often did.

“What do you mean, she died?” I said, although I knew immediately after the words leapt from my mouth how ridiculous they must sound. My dad’s uneasiness was palpable. In my childhood experience, my mom would normally be in charge of braking difficult news. A sigh escaped his lips, not one of aggravation, but of quiet desperation.

“Lizzie died today, Annie.” The fact that he was calling her “Lizzie” instead of “Liz” clued me in to how serious a circumstance we were facing. Liz was too cool and mature, in her eyes, to be referred to as “Lizzie” anymore. Yet, as a child, we called her “Yibbie” first before we could pronounce the “L” that evolved her name to “Lizzie.” Liz was her “high school” name. She would be mortified at the thought that anyone would refer to her as “Lizzie” now.

But, according to my dad, Liz, Lizzie, Yibbie, Elizabeth, she was now gone from this world. The idea of purchasing my own black and white television set no longer seemed like such an important task. That day would forever be associated with grief; a giant red “X” struck across the little calendar box in my mind.

*****

Because of Liz, my impressions of long term hospital stays did not have happy endings. They were a slow and emotionally painful journey. As we wintered with Isabelle, we too followed a slow and painful path. Our greatest hope and deepest fear, both revolved around the ending, tethered by heartstrings, pulling us in both directions.

And so with that childhood reference to M.A.S.H., I came to the notion that we were wintering with Isabelle. Maybe because M.A.S.H. took place in a hospital of sorts as well, the idea of wintering simply stuck. As I would lie in the metal hospital crib at night, curled around my baby and mindful not to put weight on any of the tubes that connected Isabelle to the machines, and to life, I would often think of my sister Maria and me, falling asleep to the dim black and white glow of our television set, wondering silently to ourselves what tomorrow might bring.

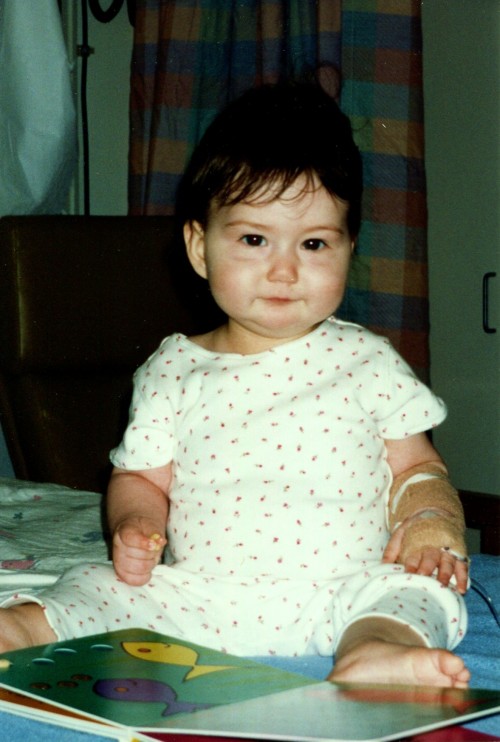

Isabelle is doing very well these days, cancer free, thriving. Grateful thanks to her mother, Annie, for sharing her story of how childhood cancer has impacted so much of her life.

If you’re looking for all of the posts in the Childhood Cancer Stories: The September Series, you can find them catalogued HERE.

If you don’t want to miss a single child’s story, you can subscribe to my blog. Please and thank you!

Type your email address in the box and click the “create subscription” button. My list is completely spam free, and you can opt out at any time.