September is Childhood Cancer Awareness Month. Each day I will feature a different guest blogger who will generously share their personal experience with childhood cancer. Stories are always more potent than statistics. The hope is that by learning about children with cancer, readers will be more invested in turning their awareness into action. Read more about this series and childhood cancer HERE.

By Cyndi Yanke

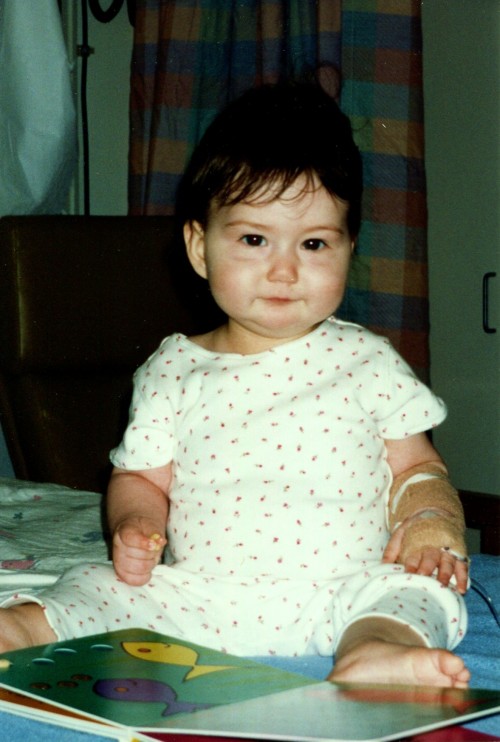

Owen is 8 years old and obsessed with all things super heroes. This could be because he has been my hero since he was diagnosed with a rare brain tumor at 13 months old.

I remember it like it was yesterday. On that Monday night we heard the devastating words no parent should ever hear, “Your son has a large mass in his head, we think its cancer.” What was my response? “We need to go home, it’s his bath time, then he needs to go to sleep in his own bed, I will call you in the morning.”

It all happened so fast. The symptoms started on a Tuesday and he was diagnosed the following Monday. When the pathology came back it was AT/RT, a nasty brain tumor with a very poor outlook for kids under the age of 3. Once he started treatment I started looking for other kids with the same kind of tumor who were long term survivors. There wasn’t a lot. I looked at that as, “Well, someone has to be in that 5% survival rate, why not Owen?”

He was in treatment for about 6 months, including one resection removing about 70% of the tumor, two rounds of chemo with stem cell harvest, another surgery to remove the remainder of the tumor, Intrabeam radiation, then three rounds of high dose chemo with stem cell rescue after each round. To look back at it now 6 months is not a long time, but back then time was a lot different. An hour lasted what seamed like days, a week was more like a month, a month I couldn’t even think about things like kindergarten.

Childhood cancer can bring out the best and worst in people. The second those words came out of the neurosurgeon’s mouth, I knew it was all on me. As we drove home that night we had to stop and pick up some new prescriptions before we left Milwaukee. My now ex-husband tells me to go to someplace where he can also get some alcohol,and not the disinfecting kind, but the ‘I need to get drunk’ kind. He spent most if not all of the six months we were in and out of the hospital at the bottom of that bottle. Well, many different bottles, and some cans too.

I knew I would be the one to stay in the hospital with Owen night after night. I knew I would be the one talking with the doctors at all hours of the day. I knew that ultimately I would be the one making all the big decisions. I knew I would be the one there when Owen needed me. I was ok with that.

In order to do that I shut down. There was a handful of friends I could talk to. You could hear it in their voices, the ‘I don’t know what to say because her baby has cancer’ tone. It was hard to hear about others’ day-to-day life. Everyone else’s life was going on like nothing happened, as our lives were hanging on by a single thread.

I can look back now and see what a completely different person I am today compared to back then. I thank childhood cancer for that. I found my voice, which I needed to use more than I would have ever expected to make sure he got the care he needed and deserved. I don’t know how many times I said “You choose to work in a hospital for children, we did not!” Looking back after 7 years, I was a pain in the ass. I’m okay with that. Most of the worst days of my life were spent there.

If having a rare brain tumor wasn’t enough, seizures entered into our lives about a year after diagnosis. So along with the routine clinic visits, MRIs, and labs, we added EEGs, and more medication. We tried multiple medication combos, with no luck controlling them. They started off lasting maybe fifteen seconds, once or twice a day, to being fifteen minutes long, multiple times a day. Our lives were spent staying close to home or the hospital. After a year of seizures with no relief in sight, surgery was suggested.

His seizures were caused by some scar tissue from his second resection that included Intrabeam radiation. I assumed they would just need to remove the scar tissue. I got a call form the office to remind me of his pre-surgery appointment, a day before surgery. One word stuck out in the conversation, hemisphrectomy. I did a bit of research on surgeries to stop seizures, so I knew what she was talking about, but she must have confused us with another kid. Nope, they planned on taking out the entire left side of my sons brain! Are you f-ing kidding me?

I told them to cancel everything. I had some phone calls to make. Second and third opinions to get. We went to see some doctors in Madison and our team in Chicago. It was only until I talked to all of them that it became clear that if I wanted any sort of life for my son, a hemisphrectomy would be the only thing that might help.

We went into surgery expecting another miracle. We were pros at this now, hospital veterans, we had this in the bag, right?. Not so much. We were in the hospital for a month straight. After a two year break from hospitals, it made it hard to settle back in. It was a different floor, different circumstances. With cancer it was a matter of life or death. With surgery for the seizures, this was a choice. That made it harder. Since it was my choice, I was overwhelmed with guilt. It was my fault he was in the hospital. It was my fault he had tubes draining out of his head. It was my fault that Owen couldn’t walk or eat. It was all on me. Looking back, obviously I made the right decision, but I didn’t know what the outcome would be. He is still seizure free five years later, clearly the right choice.

So now here we are almost seven years off treatment. Over seven years cancer free, five years seizure free. All of this in an eight year old boy. To look at Owen, most people notice he doesn’t use his right hand right away, he walks with a bit of a limp, he is a little on the drooly side. Owen gets extra help in school with math and reading, we continue to do PT or as Owen calls it “physical torture” and OT, or “Owen torture” as he calls it. This is our normal.

What have I learned with all of this? Hold him close, tell him how much I love him, enjoy the moment. There are too many families who have lost their children to cancer. We have a pretty large group of familes we are close to, mostly AT/RT families. I am thankful for them. Grateful they get it, they really understand what our life is and was like. We celebrate all of our successes, we listen for the tragedies, we are a family bound by a common enemy — childhood cancer.

All in all, our life is pretty good. Owen is an amazing kid with an amazing personality. He has the imagination of 100 kids. He has more fight in him than anyone I have ever known. What do I have? Owen. I have everything I need.

Owen and his Mom are both super heroes in my book. Our kids shared an oncologist (the fabulous Dr. Stew that you will hear from later this month) and they keep us in pumpkins every October to honor Donna’s death anniversary. We are grateful for the many friends we have made in Cancerville.

If you’re looking for all of the posts in the Childhood Cancer Stories: The September Series, you can find them catalogued HERE.

If you don’t want to miss a single child’s story, you can subscribe to my blog. Please and thank you!

Type your email address in the box and click the “create subscription” button. My list is completely spam free, and you can opt out at any time.