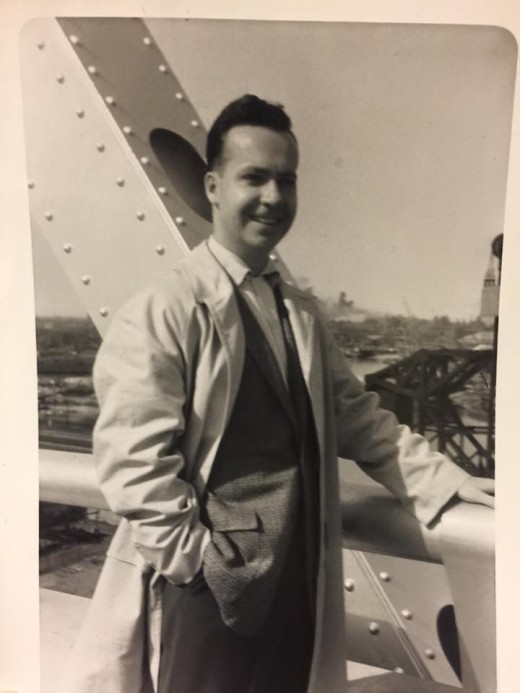

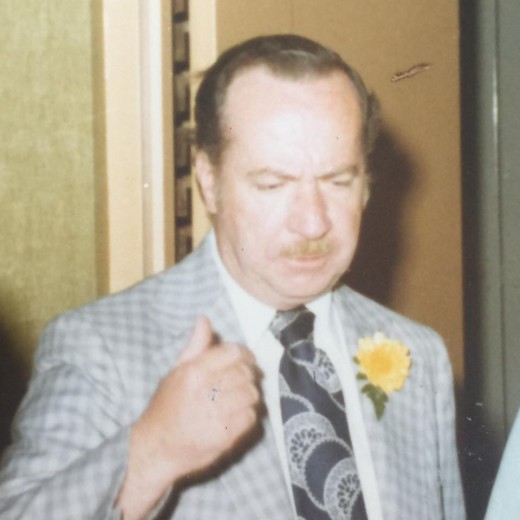

This is the third in an occasional series where I will try and capture some of the life lessons my Dad (Da to his grandchildren) taught me through the years, the goal being to preserve them for his children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews.

Lesson 3: “Walk into every room as if you belong there.”

I have written before about how my Dad was as comfortable talking to a king as he was a pauper. In my suburban Chicago childhood, that played out in watching my Dad approach and begin conversations with Chicago mayors and Illinois senators as easily as he would a panhandler. For some reason, that always embarrassed me.

It would play out frequently in my childhood, me trying to slink into some invisible corner as my Dad inserted himself in places and with people he had no business being, or so I believed. The story is as old as time, honestly — a child being embarrassed by their parent’s actions, but remembering those moments, man, the struggle was real.

On one summer vacation, we visited my aunt and uncle in Washington, D.C. My uncle had a senior position at the Federal Reserve, which was, from my 7th grader eyes, a majestic position at a majestic building, integral to the functioning of our country. Important stuff happened there that I didn’t begin to understand. After a day of capital sightseeing, all of us sweaty and tired, my Dad insisted on going to visit my Uncle in his office, hoping my brother and I would see for ourselves and appreciate more fully where such important financial policy occurs.

Ugh. It was a 7th grader’s worst nightmare.

And, as the story played out, my Dad basically willed his way into the bowels of the Federal Reserve, his two kids in tow, vacillating between sweet talking and strong arming every security officer he met along the way. Why? Because he belonged there. He belonged everywhere, was the thing.

There was the time he campaigned for Barack Obama at Chicago’s South Side Bud Billiken Parade. If you’re not from Chicago, perhaps this doesn’t strike you in any way at all. If you are from Chicago, you appreciate that the Bud Billiken Parade is a longstanding proud African American tradition, a parade that is decades old and whose origins were to celebrate the African American child and provide them with a sense of being special and enjoy a celebration in their honor. Now imagine a 75-year-old white man campaigning for who would be our nation’s first African American president there. And I haven’t even told you the part where he ran into Common and his entourage during that particular day.

There was the time he carefully explained to me that if you’re wearing a suit and looking spiffy, with a determined and distracted look on your face, that no one would question you, because, of course, clearly you belonged where you were going. He encouraged me to practice that look and gait, to hold myself with authority and purpose, especially when I was seeking entry someplace. He was part hustler, my Dad, there’s no question about it.

Some of his favorite people were the security guards he would sweet talk and cajole and charm to get into places most other folks were restricted from going. His greatest enemies, thorns in his side, were other security guards who weren’t buying whatever jive my Dad was selling that day and would use their authority to restrict his access to places he believed he belonged. Oh, did those security guards get his proverbial goat. He would rail on them, as he walked away, complaining that they had a power complex and felt inferior, so would abuse whatever little power they did have.

I had a front row seat for so many of these interactions my entire life. You never knew if they would turn out in joyful satisfaction or fitful anger.

As I look back and think about the lessons my Dad has taught me in my life, those lessons I want to pass on to other generations of my family, there are inevitably some cringe worthy moments. That was my Dad. Sometimes he could make you cringe. I could sugar coat the memories and focus solely on the victories where my Dad and his entourage of my brother and I were permitted entrance to some pretty incredible places and met some pretty astounding people, the moral of the story being to own your pride and your place, but that would only be half the story.

The other half of the story, the not so pretty half, was a white man who wanted what he wanted and believed he should have it, well, because. Rules be damned. Come to think of it, there are some pretty important lessons there, too, even if they are not the lessons my father intended.

My takeaway, as an adult, is this: Have pride in yourself, carry yourself, always, with purpose and dignity. Know that you belong in this world, whether that be in the company of movers and shakers, the political and financial elite, or if your audience is less grand, in the company of the poor and indigent. But don’t ever get so big for your britches that you think the rules stop applying to you. You are one of many, no better, no worse. And if you start to convince yourself that rules no longer apply, that your needs supersede those around you, well, check yourself, my friend, as you might need a wake up call.

I think my Da could embrace that lesson, even if he found it hard to practice himself.