September is Childhood Cancer Awareness Month. Each day a different guest blogger will be featured who will generously share their personal experience with childhood cancer. Stories are always more potent than statistics.

By Erin Miller

In February 1983, when I was 5 years and 9 months old, my parents heard those words that no one wants to hear, “Your child has cancer.”

The months of unexplained fevers, lethargy, back pain, the hard, large lump my father felt in my left side while giving me a bath, now had an answer. We were sent two hours away to the nearest children’s hospital, which would become a regular part of our lives for so many years. There I had surgery and began a regimen of chemotherapy, and several rounds of radiation therapy for stage III Wilms’ Tumor.

What has it meant to be a childhood cancer survivor over the last thirty-one years?

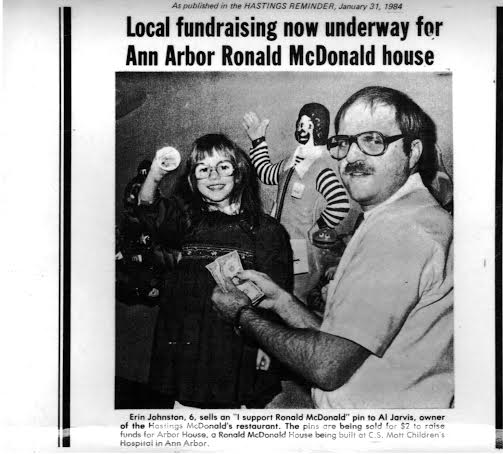

As a child, I didn’t want people to really know, because I felt different. I wanted to be normal. Now, that was something that was rather hard to prevent from happening, considering I lived in a very small Michigan town, where my dad was the editor of the local newspaper. The newspaper ran a story on how we helped raise funds for the first Ronald McDonald House, in Ann Arbor, where I was treated. Everyone already knew.

When we moved about an hour away when I was twelve, I thought that would be my chance for no one to know. But, then a daughter of a woman in my mother’s La Leche League group was diagnosed with the same exact cancer. So, of course, my mother shared my story. When my annual follow-up appointments to the clinic would arise, my friends would ask, “Why are you going to the doctor in Ann Arbor?” Explanation soon became matter-of-fact and just a part of who I was.

I realized being a cancer survivor made me unique, so maybe I should embrace it.

When I became a teenager, I began to process the reality that cancer treatment does not always end in survival. I went to church camp the summer after 7th grade grade. A particular Bible passage talked about death, and it was like a light bulb went off in my head. People die from cancer. I could have died. Other kids have died! Why did I live and they didn’t? What was different? These are questions that don’t ever get answered. I realized that there is such a thing as survivorship guilt.

I went to a music/arts camp after 8th grade and one of the students did a monologue about a girl with leukemia. I will never forget sitting there in the open air auditorium, the tears welling up, my heart palpitating, hands sweating, the beginning of panic setting in as this girl acted out her piece. I had to leave.

My body was reliving its own experience in her words. It was my first experience like that, but not my last over the years. Even now certain things will trigger a physical response in me, most often it is medical-related; such as hospitals or blood draws, but certain smells, words, songs can do it too. I realized the body remembers in ways the mind forgets, especially when you are treated for cancer at such a young age. You sometimes don’t even know how to voice everything.

When I was newly married, in my early twenties, and the realities of the late effects of my treatments began to set in, I began to deal with some anger and depression. My radiation treatments left me with acute ovarian failure. We tried in-vitro fertilization with donor eggs, with my older sister going through the donation process. However, my uterus was also so compromised not one of the three cycles worked. We were told adoption was our best route to a family. Infertility after cancer is hard. I was never angry at my parents for choosing the treatments to have me live, but I was angry at the results. It certainly didn’t seem fair. Not only did I have to go through cancer treatments as a child, but what made me well took away something I longed to experience, pregnancy, motherhood with children that share your traits, your nature. I secretly began to think maybe there was something inherently wrong with me, hence cancer, no pregnancies.

Depression began its insidious takeover in my life. I realized, twenty years after cancer, that its effects were still very much present in my life, physically and emotionally. Depression was an undercurrent in my late twenties/early thirties. My doctor prescribed an antidepressant, which I took faithfully, but I pushed away most attempts at counseling.

My husband and I began the adoption process, choosing domestic adoption. we wanted our child(ren) to have a connection to their birth family and history. We were chosen once after a year of waiting, only to have the mother decide to raise her baby, as was her right. I was devastated, thinking maybe I really am not meant to be a mother at all.

We began our second year of waiting, which also included a litany of family and friends announcing pregnancies. Babies were due left and right. I hid my feelings of sadness, went to baby showers and hospital visits to see new babies. At the end of the second year of waiting, we decided to change adoption agencies. We were chosen the same day we were officially switched! Our daughter was born three weeks later and motherhood became one of the best things that ever happened to me.

It didn’t cure my depression, though. That took a serious turn for the worse when our daughter was a year and a half old, and I finally agreed to counseling. In the midst of counseling, I realized that I had believed, since I was 5, that I had caused all of the pain, anguish, sadness my parents and sisters felt by having cancer, but because I was young and unable to vocalize those words and feelings, I internalized them all for years and years. Those words and feelings became a part of my subconscious, and inside I believed that this made me a bad person.

It took six years of regular counseling to sort through it all, and I realized that nothing I did, or anyone did, caused my cancer to happen. I finally grasped that I am a survivor, not a failure.

We have since adopted a second time, another daughter. The two of them are my whole world and I would do anything for them. I work hard to not overreact to sickness, but then my older daughter went through a series of off and on stomach pain, headaches, leg pain, low grade fevers recently. When our doctor requested blood work, my heart raced and my head swirled with the worst case scenarios. The blood work was normal and a long running virus was the most likely cause. I have realized that motherhood is one of the most wonderful and scariest things as a childhood cancer survivor. You know what the worst could be because it happened to you as a child, and you do not want it to happen to your child.

Now, in my late thirties, I look at my life, I am thankful I am a cancer survivor. It has shaped so much of my life. Yes, it has given me a scar, one kidney, anxiety and depression. But it has also given me more compassion, more empathy, more strength, a recognition that we are given just one life to live, and how we live that life for our faith, our family, ourselves is so important.

I try to use my survivorship as a way to advocate- an area in which I would like to become more involved. As a result of my childhood cancer, I have been able to connect with many others, primarily thanks to social media, who share similar experiences.

Don’t miss a single installment of the 2014 September Series! Subscribe!

Type your email address in the box and click the “create subscription” button. My list is completely spam free, and you can opt out at any time.