I live in Chicago, one of the most racially and class based segregated cities in America. Knowing this, and loving this city despite its deep flaws, when we purchased a home, my husband and I opted to find a neighborhood that was diverse, both economically and racially. It was no easy feat.

When we started raising children together, including one that came to us through adoption, the racial divide was seen in a stronger light. When you adopt, part of the process is sitting down and considering who to adopt — a sick child? a foster child? an older child? an African American child? a Latino child? a biracial child?

I can’t lie — having to provide an answer to those kinds of questions is like putting a magnification mirror right on up to your heart and conscience. Answering those questions also forces a discussion about race that many folks might never engage in through their lives. But why? Why don’t we talk more about race in America? I think the honest answer is because it is hard. Really hard.

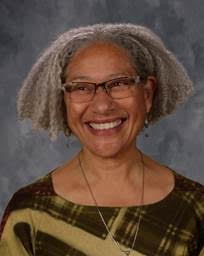

Recently, I had the opportunity to interview Dr. Jean Robbins, Head of the Early Childhood Division at Catherine Cook School in Chicago, who has expertise in this area. If you want to talk about race and children, this is your gal. Dr. Robbins has developed a six point list of tips about how to address the subject with young children. I find her tips to be concrete, accessible, and easy to implement. Here they are:

TIP 1: START EARLY

By the age of 3, children are noticing physical differences among people, including skin color. Many parents cringe when children (loudly) comment about these differences, when they should instead, very matter-of-factly, open up the discussion and know that their children can handle its complexity. For example, parents can simply explain to children, “an African American is someone who usually has brown skin and has great-great-grandmas or grandpas who came from Africa. All of our families came from a different country at some point!” Parents should also be aware that children can be very literal when it comes to race, so anyone with brown skin might then be African American to them.

TIP 2: DO NOT SHY AWAY

Many parents are afraid to say the wrong thing, so they avoid conversations about race, but their silence sends unintended messages to kids. Silence tells kids that there is something wrong with or negative about people of color. Talking about race, on the other hand, stimulates curiosity and minimizes fears about race.

TIP 3: DRAW THE BIGGER PICTURE

There are daily opportunities to celebrate diversity and there is no need to wait for Black History Month. For example, taking your kids to museums, restaurants and cultural events across the city, or, watching movies and reading books about children from other cultures are all ways to increase awareness. Some museums, libraries, and cultural institutions offer free informative events for families during Black History Month.

TIP 4: BROADEN THE LESSON

Children like to learn about topics as they relate to their own lives. By framing American history around ideas of conflict, fairness, and sharing, even young children can understand lessons about any historical period. Keep it simple, but be accurate and honest. For example, maybe you pose a question to your child: “People who owned slave didn’t want to do the hard work and didn’t’ share the money with the slaves. Do you think that was fair?” This will open up broader discussions and encourage critical thinking.

TIP 5: MODEL LEARNING

Parents are examples for their children, and can be models of learning and curiosity. It is okay for parents to admit when they do not know something, and then suggest to their children that they find out together. Parents should not be afraid to say, “let me think about that” or “I’m not sure, let’s find out together!” A family visit to the library is a great way place to start.

TIP 6: ENCOURAGE SELF-EXPLORATION

We all bring diversity in one sense or another. Parents and teachers can encourage students to explore their own identities and reflect on what they learn about themselves. At Catherine Cook School, a Diversity Committee composed of parents, teacher, board members, administrators and staff members work together to integrate diversity themes, topics and activities into the curriculum starting in preschool. Together, we can teach children about their cultural and ethnic identities, even through cultural traditions such as cooking or the clothes we wear.

After our conversation, I was struck by just how rare it is to have a discussion solely about race, especially with someone of a different race. We need to change that.

One thing that struck me in our conversation was hearing Dr. Robbins acknowledge that for children, it can be hard to make the right choices — hard to share, hard to include all children, hard to always listen to our parents. It is the same for us as adults. It can be hard to always do the right thing or make the right choices. There is a parallel process there that we should not discount. Discussion about race and acknowledging differences are hard, but so very valuable in the long run. From Dr. Robbins, “I’m the same. My experience is different. What is the sweet spot where we can connect?”

“Children will yell out. ‘You are black!’ ‘Why is your hair so fuzzy?’ It will frighten teachers and adults. But they are celebrating words and language. Encourage them to express their curiosity. Children notice reality.” Amen. Don’t assume, for whatever reason, that there is no reason to discuss race with your children. As Dr. Robbins suggests, “Be ready to talk. Ask questions, guide conversations, provide experiences, read books. There is no excuse for not accessing materials about others.”

Dr. Jean Robbins has been the Head of the Early Childhood Division at Catherine Cook School since 2007, and has established best classroom practices, curriculum and supervision measures to make the school a leader in high-quality early childhood programming. Dr. Robbins holds a doctorate in Child Development from the Erikson Institute, an M.B.A. from Columbia University in New York and a Bachelor’s degree in Psychology from Smith College. Before coming to Catherine Cook School, she worked as a researcher on a variety of studies, including a national home-visiting program, an early childhood teacher preparation and diversity study in the U.S., and an early literacy and play study for Yale University. Dr. Robbins also served as Director of the Parents as Teachers First program at Chicago Public Schools, which was a citywide early childhood home visiting program.